THE GATE THEORY OF PAIN I: The Multidimensional Experience

Have you ever hurt yourself and only noticed the pain minutes or even hours later? Or had a headache, even though the brain has no pain receptors? Or felt pain in one part of the body even though the actual injury occurred elsewhere? These are just a few examples of why physical injury and the subjective experience of pain are not always directly related.

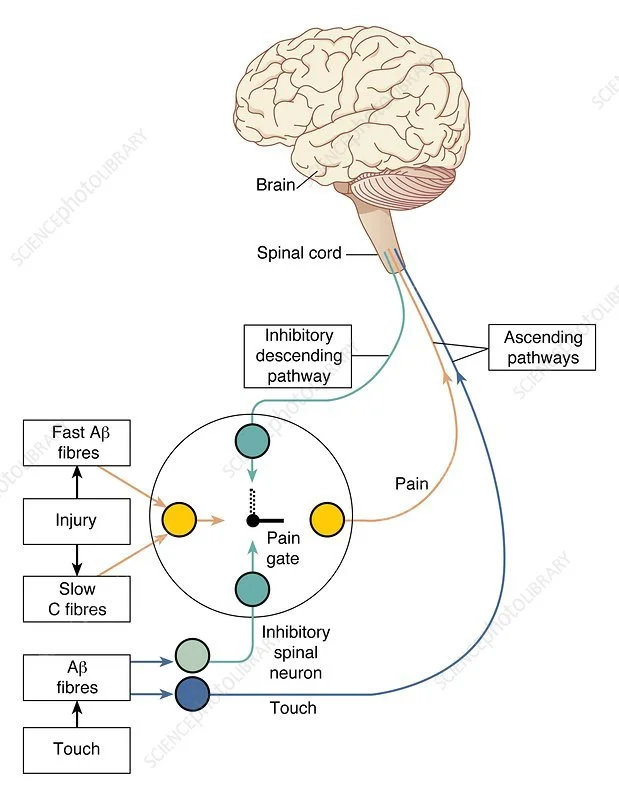

This distinction is at the heart of Melzack and Wall’s Gate Control Theory of Pain, first published in 1965. Their revolutionary model helped explain why pain is not simply a direct response to tissue damage but a complex, dynamic process involving both bottom-up sensory input and top-down modulation from the brain. The theory remains foundational in pain science today, and provides a helpful framework for managing pain in impact play.

Pain Is Not Just Physical

Pain is not a linear reaction to injury; it's a multidimensional experience shaped by culture, learning, attention, context, and emotional state. Anxiety, for example, increases pain perception—anticipation can make a mild sensation feel sharp. In contrast, relaxation or distraction can significantly reduce the sensation of pain.

Even the perception of control plays a powerful role. In a classic experiment (Mowrer & Viek, 1948), rats were exposed to electric shocks. One group could end the shock by jumping, while the other had no control over its duration. Although both received the same amount of shock, the rats who had control were less stressed and continued normal behaviors like eating. This illustrates that our nervous system reacts not only to stimuli but also to how we interpret and engage with those stimuli.

The Gate Control Theory Explained

Gate Control Theory Of Pain, Artwork is a photograph by Science Photo Library

https://fineartamerica.com/featured/gate-control-theory-of-pain-artwork-peter-gardiner.html

Melzack and Wall proposed that pain signals from the body must pass through a kind of "gate" in the spinal cord, which can either amplify or dampen the signal before it reaches the brain. This gate is influenced by various factors:

Competing sensory input (e.g., touch, pressure, warmth)

Emotional and cognitive context (e.g., fear, attention, meaning)

Descending signals from the brain (e.g., expectations, memories)

When you receive an impact during a scene, your nociceptors—the sensory neurons that detect harmful stimuli—start firing rapidly. But whether you interpret that signal as painful depends on what happens next: signals pass through various processing centers in the central nervous system, including the limbic system (emotion), hippocampus (memory), amygdala (fear/avoidance), and the frontal lobe (context, meaning, intention). The latter, the involvement of the frontal lobe explains why many animals react to pain reflexively (by fleeing), while humans can override that impulse when pain is meaningful, consensual, or ritualized.

Pain perception is a time-sensitive act, because nociception changes over time, which is key in building up the impact journey. Why the timing matters and how to use it to mitigate the feeling of pain while deepening the experience is what the second part of this article is about. Then we will explore how the central nervous system actually learns to cope with pain over time.

It is only by understanding how the body processing pain and what the underlying neurochemistry is that it becomes understandable that the body turning (bearable) pain into pleasure is a natural human reaction.